A poem about viruses?

I wrote this back during the COVID-19 pandemic. Still relevant, I think…

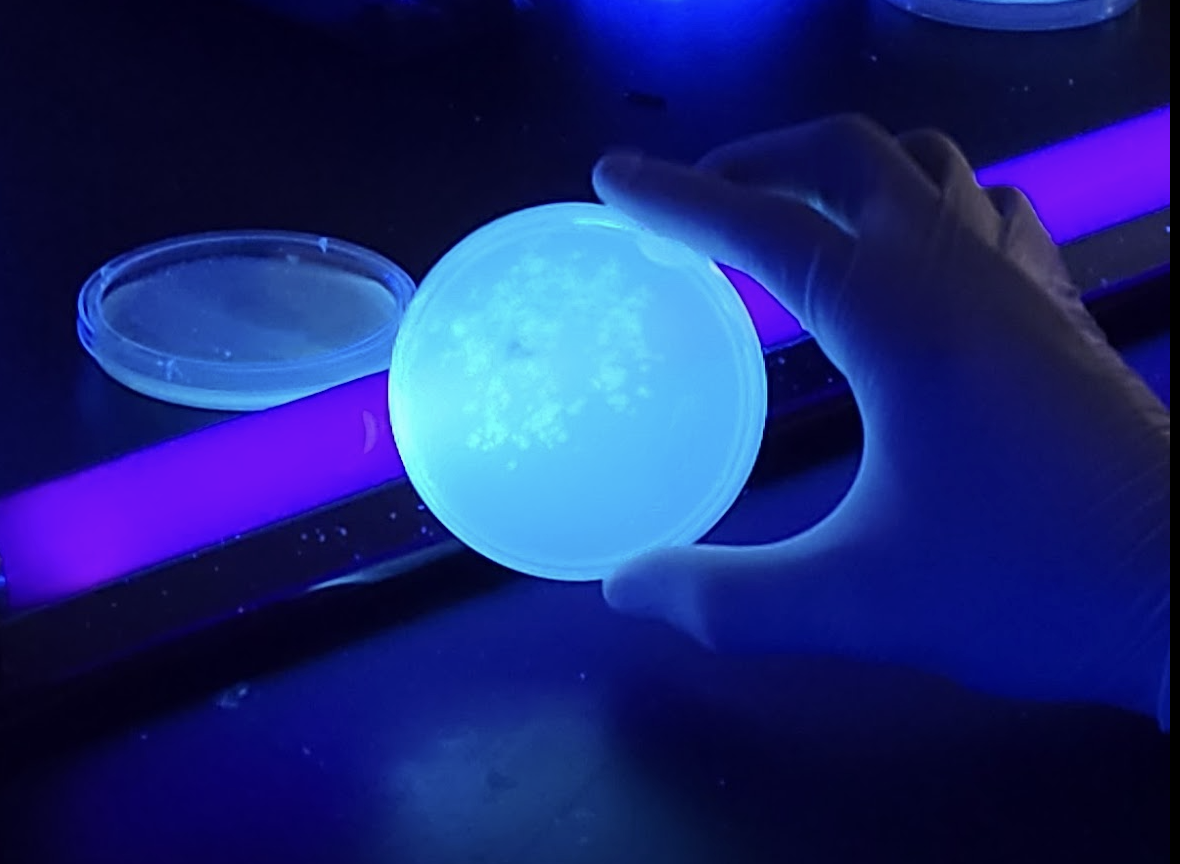

Photo taken by me, from a bacterial transformation via viral vector lab I did with students a few years back

Combinations of the four,

A, C, U, and G.

To build an RNA World, the oldest code

Of life’s bounty,

From beauty to beast and the range

Of Harriet’s creatures.

In the blink of an eye or

A bat’s wing,

A deadly code does thus refine

And failures are fickle teachers.

A virus born of the four,

Adenine, Cytosine, Uracil, and Guanine.

Pathogens persist at astonishing pace,

But to sustain a pandemic requires such

Insidious constituents

Of limited range and the same fucking face.

Authoritarian, Capitalism, Uneducation, and the GOP,

The horsemen of the Broken States.

Combinations of the four,

A, C, U, and G.

To break the New World.

When it is all too overwhelming

I had some thoughts today pertaining to the present state of things in the United States and the feelings of hopelessness we all often find ourselves in.

21st-century humans have this incredible gift that humans of centuries past lacked: we can choose our communities.

Though our minds are still wired to be altruistic for only a small, close few, they contain no boundaries to the breadth of our willingness to connect with others. We so often go beyond our wiring to feel the love of a global community. But just as empathy expands to many and brings with it connection, pain and fear also abound. The vulnerability we experience by daring to care for this massive global community is raw and unrefined because it certainly wasn’t forged by evolution.

Some humans can’t do it. Some cannot breach the empathy boundaries of their own likeness. There is no vulnerability, no risk of having to adapt or self-evaluate under the light of a far larger world than their Sapien minds are programmed. So they viciously protect that boundary, at every fathomable cost.

So what do we do? Protect ourselves by reducing our community to only those with whom we share a common vision, or expand our vulnerability to where empathy is met with pain?

The hope lies in this simple fact: you don’t have to choose. You don’t have to let false dichotomies whittle down your sensibilities into simplistic categories that only serve the comfort of others, and to paralyze you into inaction that only serves the status quo.

You can focus your attention, time, and love on your own little circle of like-minded visionaries, AND also take action to improve the larger world community. You are not narrow-minded for choosing to focus most of your time and energy on that which you can most directly affect. You alone are worth it. The world is filled with rough terrain, and not all of it is capable of cultivation.

Love the land, but don’t water barren soil.

Keep nourishing your community and yourself.

You matter.

(Can also be found in my Substack, A Mari Ad Astra)

For Jane.

This loss breaks my heart beyond words, but what an unbelievable 91 years.

The first time I saw Jane Goodall speak was circa 1992, in Spokane, Washington. My mother took me to see her (I would take my mother to see her speak in Tampa in 2014). Jane was giving one of her hundreds of talks on not just her work with the chimpanzees of Gombe, but on the larger lessons of the plight of all Earthlings. My mother bought me a souvenir, a print featuring all of the chimpanzees from her research in the 1960s, and I memorized all of their details: David Greybeard, Flo, Flint, Goliath, Frodo, Faban, and others. I was awestruck by her bravery in venturing into the lives of such powerful creatures; at that time in my life, my obsession was orcas, and I wanted to understand them and connect with them as Jane had done with primates. Having her as a role model, both as a woman and as a scientist, was transformative for my young self. As a child, I always had a sense that animals were not so different from humans as society perpetually placed them, that my sense of “personhood” never hit a hard line after other humans; it always included other species of animals. Jane Goodall validated this sense of mine that was at odds with what society told me. Thank you, Jane.

I took this blurry pic of Jane when she gave a talk that my mother and I attended in Tampa, 2014.

Into my young adulthood, I learned from Jane what it means to be not just a scientist, but also a naturalist and a feminist. That drawing from intuition is a strength and can inform data collection and analysis. That solving environmental problems starts with solving human problems. That engaging with our world - human and non-human alike - must always start with seeking understanding of it. That empathy and compassion are necessary qualities in engaging in the natural world. As I read more about Jane’s life in Gombe and the challenges she faced in the scientific community, especially as a young woman without an academic pedigree, I began to feel more empowered in understanding the ways that patriarchal systems and misogyny had negatively impacted me both personally and in my academic pursuits as a scientist. She persisted in pushing back on the [entirely male] establishment when they decried her evidence because it didn’t align with pre-conceived notions of what separates humans from animals, and condemned her on the basis of her age and gender. Jane’s resilience in her own work, and her broader feminism, helped ignite my own, and still inspires my capacity to be a “difficult woman” as much as necessary. Thank you, Jane.

One of my personal favorite Jane quotes.

This last summer (2025), I was on my big “Sea & She trip”, which included time in Tanzania. While on that leg of the trip, I read Jane’s book The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times, co-authored with Douglas Abrams, which I blogged about here during my trip. It was beautiful to read Jane’s words and be inside her mind somewhat while in her treasured land of Tanzania (though I never got anywhere near Gombe and saw no chimpanzees). During my time on Zanzibar and around Arusha/Ngorongoro, I saw evidence of social and environmental progress that must be connected to Jane’s work, directly or indirectly.

In her dedication to the plight of the chimpanzees, Jane quickly learned that human needs had to be met in order for sustainable environmental action to occur. Poaching wouldn’t stop if there were no financial alternatives for the people of Gombe. Deforestation wouldn’t be reduced if there were no other sources of income but logging. The people of a community cannot care for the environment if they are without clean water and food. And education is paramount for all of the aforementioned to occur. So Jane set her efforts on not just stopping the killing of chimpanzees, but also fixing the desperation in the human communities that results in the cycle of suffering for all beings in an ecosystem. Reciprocity is the key concept, and Jane could see this clearly from the beginning. Her Roots and Shoots movement builds up communities through educating and empowering youth. The Jane Goodall Institute continues conservation efforts around the world, especially focusing on endangered species of East Africa.

What I noticed in Tanzania, whether I was talking to a scientist at the SCUBA shop on Zanzibar or a cab driver in Arusha, was two major things: 1) Tanzanian women and girls now have more rights when it comes to education, employment, and motherhood than we have in the US (I know that isn’t a high bar right now, but still, progress for Tanzania), and 2) sustainability efforts and women-run businesses had increased in tandem (this includes the seaweed and sponge farming women I observed on Zanzibar). While I know there are many variables to account for these observations, I cannot help but see Jane’s hand.

In Jane’s Book of Hope, she gives an incredibly compelling case for hope, which is particularly poignant given the [gestures vaguely at all of the nonsense we are all currently living through]. She is clear that hope is not a passive whim, but rather active engagement. We can all engage in this world in the uniquely incredible ways that each of us can bring, and be a testament to Jane’s hope. It’s not going to be easy, but engage we must. Always.

She gave the world more than can ever be measured.

Thank you, Jane.

Wanna take my trip on Google?

I’m frequently late to the game when it comes to technology.

Google Earth Voyager was launched in 2017 as an educational and general wanderlusty tool. You can take a little journey through a specific place, time, issue, or culture by zooming around on Google Earth. Photos, videos, interactives, articles, and 3-D street view accompany this trip. The other cool thing is that you can make your very own! This has obvious applications in the classroom, but you can see where I am going with this.

Yes, I made a Google Earth Voyage for The Sea & She! You can zoom around to each of the places I visited, click through my photos, information for each of them, and I placed links to this blog as well (my web tech-ing is eating its own tail). It was fairly easy to do, especially if you are familiar with the Google suite. Though a good presentation tool that I intend to use at my school (The Cambridge School of Weston) to showcase my trip, it is a bit clunky for viewers to experience. Hence, I’ll talk you through some of it.

FIRST! You’ll want to click on the “Table of Contents” on the lower left. Then, to visit each location, double-click on it. It will “zoom” to that location.

See the Table of Contents on the lower left from which to select the different locations.

Then, you can click on the markers on the map itself, and the panel on the right will have photos and information for that marker. You can click on the arrow to see each photo.

The panel on the right takes you through the photos and descriptions of each different location marker on the map.

Maybe this will be fun and interesting! Maybe it will be annoying and difficult to navigate. I hope it proves to be the former.

Enjoy!

Subscribe Button! And Summer Reading

It’s been a minute!

I’d say that I’ve had some quiet downtime since my big Sea & She trip, but the last month has been anything but. I had the sincere honor of co-officiating my brother’s wedding in Maine, and then took my annual pilgrimage West for Star Trek Las Vegas. As always, it was joyful and exhausting all at once, and regardless of what is happening in our world at large, time with Trekkies leaves me full of hope. There is much more to say on this topic, and I will at a later time when my brain cools down a little.

For now, big updates! I am in the process of writing my book on the Sea & She, and continue to be grateful for every second of the trip itself, and for the many tidbits of research that have come my way that validate much of what I learned.

I have also now set up a subscribe button on my blog - something I am sure I should have figured out a long time ago, but c’est la vie. So please, please subscribe below! You’ll get my new blog posts in your inbox, as well as infrequent updates about my book.

Finally, in between all of the travels and goings on, I have enjoyed some excellent reading this summer and wanted to know what books everyone else has been digging into. Here is what I have been/am in the process of reading:

What about you?? What has been good? Transformative? Terrible?

Leave comments below! Yes, I figured out how to add that, too. I know, I’m learning.

I will get back soon with more frequent and substantive blog posts, as well as my personal take on these reads. In the meantime, stay cool out there and enjoy the rest of the summer.

LLAP

Stranger in a Strange Land

As I come to the end of “The Sea & She” adventure (currently in Dar es Salaam preparing to fly to Dubai, and then home to Boston) I wanted to reflect on my first experience traveling internationally alone and offer whatever passes as words of whatever-you-need-them-to-be for those who may do the same. First, a little about me and my life as a traveler.

One of our haenyeo instructors took this picture of me on Jeju. I so appreciate it because it perfectly encapsulates how I feel about both the ocean and solitude: powerful yet utterly serene.

Traveling, both within my home country and internationally, has always been a significant part of my life. I owe this to my parents, both for my father’s career as an airline pilot and for my mother’s upbringing in the Alaska bush, instilling in her both a different flavor of aviation and an avid sense of adventure. When I was growing up, we traveled very frequently, and mostly on airline employee passes as a tier below standby passengers. This meant that we were never guaranteed to get on a flight or even arrive where exactly we intended to go, and often meant sleeping in airports, sprinting across terminals to try for a different flight that had open seats, never checking bags ever, and always dressing your best, in hopes of impressing the gate agents with spotless decorum. Anyone who flies regularly has experienced the stress of a delayed or cancelled flight, or traveling standby, or similar, to be sure. But employee family flying as a lifestyle is one of those things you have to experience to fully understand.

As you might imagine, such a life nurtured several skills and/or character traits in me and my brother (now an airline pilot himself), and over the years, I have become increasingly grateful for the effect this form of traveling had on my development. I most certainly wouldn’t have agreed in my formative years; we would have traded part of our young souls for actual full-fare tickets of our very own! One might think that airline pilot children who spent their youth bouncing around on free flights would feel entitled or take travel for granted. But this couldn’t be further from the truth, at least for my family and other “pilot kids” I know well. When you watch family after family waltz onto a flight to Disney World in front of you, you’ve been awake for 28 hours watching seats get filled with standbys on 5 other flights you didn’t get on and would gladly give a kidney just to get the last seat on a redeye to Newark, “entitled” is the last thing you feel. “Indignation” might make the list. You’re just a kid, after all.

Me with my dad at our air park home next to our Taylorcraft L-2, circa 1985.

What we learned: Patience. Flexibility. A capacity to entertain yourself. People-watching skills. Fortitude when your sleeping arrangements are sub-ideal. Ability to demonstrate gratitude across cultural lines. You sometimes end up staying with your dad’s pilot friends in new places, or per their recommendations, take an off-the-beaten-path approach to a location otherwise mainstreamed with only a tourist-eye view. Really, these are solid life skills for anyone, not just travelers. And I am certainly not going to sit here and preach them as if I successfully model these abilities all of the time; I definitely struggle with them on any given day, as we all do. But I will say that thanks to my parents and the highly unique version of traveling they raised me with, when I find myself in any kind of challenge, especially as a traveler, I feel these skills pop into gear, and a calm confidence comes over me.

That calm confidence couldn’t be better exemplified than in my parents. On their 2016 Vintage Air Rally Crete-2-Cape adventure, in which they, along with my brother, joined an international roster of about 40 pilots in flying insanely cool old biplanes from the island of Crete to Cape Town, South Africa, over a few weeks, all of these skills were put to the test in spades. The fleet was detained in Gambela, Ethiopia, for two days in an old airport terminal, their tech confiscated, due to a problem with their landing permissions. Multiple governments had to negotiate their release. My parents, no strangers to aviation kerfuffles or to related uncertainty, were the voices of reassurance and optimism for other members of the group who were, understandably, anxious and uncomfortable. They engaged everyone in games, storytelling, and took it on themselves to liven the spirits of their fellow aviators when there was no clear sense of what would happen to them next. For this, they received the “Spirit of the Rally” award at the conclusion of the event, which did indeed conclude safely in Cape Town later that month. I am so proud of them, and not the least bit surprised.

My parents next to the vintage wood-frame biplane the flew in the rally, a 1928 Travelair 4000. Incidentally, in this aircraft’s records, it was once confiscated by the US government during prohibition for transporting liquor. Badass.

My feeling about travel, especially during travel, deepens in awe every time I experience it. If at any time I took it for granted, I feel that I do so less and less with each adventure. I watch those around me at the airport and am absolutely bewildered at the fact that humans from across the planet can be here, at the same time, each of us a multitude of stories, seemingly endless lifetimes passing through this place (and a terrifying diversity of microorganisms, but that’s for another blog post). I watch families interact and wonder how their upbringings differ from mine, and what we have in common. I watch someone with a religious symbol on their jewelry and wonder what their path to their beliefs looked like. I watch someone intently focused on their laptop, working, and wonder what skill set they have that I’ve never heard of. I watch someone zoned out and wonder what nonsense song is stuck in their head, along with a breakdown of how the study of orca cognition is really damn cool, and we might be on the verge of a breakthrough (or maybe that’s just me).

And airplanes! If anyone should take airplanes for granted, it’s this girl. We lived on an air park when I was a little kid, and when we moved off of it, I didn’t initially understand that there were houses and neighborhoods that didn’t have hangars for their airplanes, just like you have garages for your cars. I should be extremely unaffected when I see airplanes in the sky. I fly them too. And yet! Every time I see an aircraft in the sky, I think “holy SHIT, we upright-walking apes made FLYING MACHINES that move hundreds of miles an hour, miles high in the sky, with hundreds of people inside. INCREDIBLE!” Don’t even get me started on space stuff.

However I change with age, I so very much hope that my awe continues to increase, like this. To a silly extreme, if necessary. I want to get excited about cardboard boxes when I’m 90.

Back to the topic at hand.

Up to this point in my life, I have been all over the United States (to all 50 of them, in fact, plus Puerto Rico and the USVI), Canada, much of Central America, some of South America, all over the Caribbean, the UK, New Zealand, Fiji, many countries in Europe…I know I am painting broad strokes here when I generalize “Europe”, but you get the picture. All to say that this “Sea & She” trip hit some major milestones for me. Prior to this, I had never been to either Asia or Africa. Had never set foot in the Indian Ocean. I will now have circumnavigated the globe. And I will have traveled alone internationally for the first time, and not for an insignificant duration or set of logistical circumstances.

Traveling solo certainly has its advantages and disadvantages. I’ll start with the downsides that I personally experienced:

Getting sunscreen on the hard-to-reach parts of your back (give up and wear a sun shirt, says I).

Tours that book a minimum of 2 people (you can accept that you’ll pay for 2, the solo traveler tax that shouldn’t exist but does)

Merchants and vendors are more persistent, especially if you’re female (and Maasai who won’t stop offering you a security detail)

Getting locked in a bathroom stall at the Arusha airport with no travel buddy to help break you out and nearly missing your flight (true story, this one was this morning).

It is easier to travel solo in some cultures than others. In my case, solo travel in South Korea was far more common than it was in Tanzania, for example, and so I encountered fewer barriers to my operations. While on Zanzibar, there was persistent infrastructure in activities and meals all designed for couples or families, which is common in high tourist locations. Something I am very grateful for finding was Nomad Her, an app designed for solo female travelers to connect. Nomad Her puts on the Haenyeo Camp on Jeju and organizes a variety of other activities for solo women travelers all over the world. It is a fantastic way for solo women to get together for day trips and provides an element of safety in checking in with someone. I highly recommend checking it out if you’re a woman and looking to travel solo.

Our intrepid Nomad Her haenyeo camp leader, Soyoung (in the t-shirt) with the group of us solo female travelers and haenyeo wannabes. We now call ourselves sea sisters = “seasters”.

My upsides of traveling solo get more personal.

While I also have and do deeply enjoy traveling with friends and family (truly, no offense, my loves), in embarking on this trip, I was insanely excited for the alone time in my own head. I am quite independent by nature and sincerely enjoy a kind of solitude that solo travel provides. This version of myself that I came to discover in my solitude while on this trip was quite intriguing. Apparently, I power walk everywhere, all day. My eating habits are extremely erratic. My sense of humor is somewhat mercurial at worst, but mostly hilariously feral. I go towards whatever piques my curiosity and never stay past its expiration. My sense of myself has no clear orientation with respect to what others are doing, except maybe as an inquiring observer. I feel truly like a “stranger in a strange land”, though maybe slightly less Martian than Robert A. Heinlein might suggest. I interact with those I meet politely, inquisitively, and to the best that my extremely limited skills with the local language will allow me. After several days of not hearing or speaking my native tongue, I hear it as a voice narrating my actions. It mostly has no clear gender, though depending on my activities, on some days it is David Attenborough, on others Sir Patrick Stewart, and on the strangest days, Kate McKinnon. No, it’s not schizophrenia (though I’d gladly take all three of those rockstars in my head any day), just a better voiceover for my own thoughts. I am alone, but I don’t feel lonely. Most of the time, anyway.

I wish I had done this when I was younger, traveled alone long enough to hear the inner weird really speak to me. Some cultures actually encourage this in their young people to go off and experience independent time away from home. The Amish, for one. More and more students I teach are taking gap years before college as a way to get to know themselves and the world outside of the academic lens. There may be something to this. I wonder if I had done this trip in my 20s, as many of my peers did, would I remotely recognize that version of myself today? To those of you who did, do you still hear that part of yourself when you’re alone?

This untamed me that I am starting to listen to now, how I am cherishing her. Perhaps this is actually the perfect time in a person’s life for a solo adventure, at the bridge of middle adulthood between youth and wisdom. You know the extreme value and importance of interdependence with those we love, but also you have felt the toll it can take on a person, year after year, to not hear this inner voice that only comes alive in the absence of the others.

Whatever solo travel can give you, I recommend it. With all my heart. Go listen to that inner weird of yours. Wander by your own curious whims and nothing else. Let your mind get a little bit feral.

Until next time,

Live Long and Prosper

Orca-nized wisdom & the evolutionary advantage of grandmothering

I promised that I’d come back to the topic of orcas and why they are relevant to my study of “The Sea & She”. Funny that I should choose to do so when I am now far from the ocean, high in the hills of Tanzania near Ngorongoro Crater. It is a stunning place to reflect on the past three weeks, to be sure, and I will soon have an opportunity to see some of the legendary scenery and wildlife on a safari.

In the three vastly different regions and cultures of sea women that I have studied on this trip, there are certainly some key similarities and throughlines that I will be exploring in the book I intend to write on this topic. Ideas around family, duty, love, and how the ocean connects and empowers us as women. Perhaps the most intriguing, to me at least, is the generational passing of knowledge, especially from mothers to daughters, and the role that grandmothers play in this as they continue to work in the sea for as long as they are physically capable. Grandmothering is a crucial constant.

This is where orcas come in.

Underwater view of a pod of orcas. Image credit: Philip Thurston/Getty Images.

Orcas are a highly matriarchal society. They are led by their grandmothers, and they stay with their mothers and grandmothers for their entire lives. Families will cross paths with other families for mating, but afterwards, males return to their own mothers and grandmothers. Several ecotypes have been observed to live the equivalent of human lifespans. They are very socially and emotionally complex, as well, possessing a highly developed lobe of their limbic system that corresponds to what neuroscientists believe may be a sense of collective identity.

In other ways, they are also exceedingly intelligent, particularly in their sound perception. Orcas’ sense of touch and sight is equivalent to ours, their sense of smell slightly worse than ours, but their sound world is something on an entirely different plane of existence from ours. When it comes to what they can know, understand, and perceive, they are most definitely self-aware (by human standards) and capable of basic reasoning and problem-solving. But when it comes to our understanding of their sonar world, we’ve got nothing. I was recently reading a book called Of Orcas and Men by David Neiwert, and he quoted a well-known orca neuroscientist, Lori Merino, stating that “cognitively speaking, orcas are pretty good humans, but humans are terrible orcas.”

The orcas of the Salish Sea alone have a diversity of cultural (yes, culture) practices in their different pods that have been recorded over the years, and continue to baffle and intrigue scientists. This has included wearing salmon as hats and, as recently documented, using kelp as a massage tool.

Some of the transient Salish Sea orcas I saw while whale watching with my family.

You may have seen orcas also gain notoriety in recent years for breaking apart yachts near the Iberian Peninsula, despite not displaying any aggressive behavior or ill-will towards humans, specifically (orcas have never attacked or harmed a human in the wild). And a recent meta-study has now shown that orcas across the world have been offering food to humans.

What is going on in their complex and brilliant minds? Are they simply playing with us? Do they recognize our sentience and are trying to communicate?

Now that you know why they are intriguing and awesome, on to why they are relevant to sea women and us humans in general.

As previously mentioned, orcas are matriarchal and led by their grandmothers. They are also one of only four other species of animals besides humans that experience complete menopause (the other three are beluga whales, narwhals, and short-finned pilot whales. Some primates and small mammals experience a menstural slowing, but not a full stop). Interesting that it is just us plus cetaceans, isn’t it? Maybe we are mermaids after all.

A common question in evolutionary biology has focused on the purpose of menopause and female longevity past reproductive age. What survival advantage must this have? The most common answer seems to be the “grandmother hypothesis”: that rather than have more offspring that are in competition with her existing daughters and their offspring, a grandmother dedicates her knowledge, leadership, and resources to ensuring the success and survival of her grandchildren, nieces, nephews, etc. This appears to have been an advantage when food is seasonal and scarce, and for animals whose reproductive strategies favor fewer offspring but investing a higher degree of maternal care.

My beautiful mother and her grandson, my Jack, while looking for orcas in the Salish Sea.

Western culture, in particular, tends to respect and regard women less with age. We decline in our reproductive capacity and in the cultural definition of physical beauty, and we start to become invisible. I am beginning to experience the latter as I progress through middle age and receive fewer stares and glances in public places. I admit this is a huge relief for me, personally, but the issue of perceived irrelevance is problematic for women on a larger level.

We have something rare, something evolutionarily powerful, something we share only with these brilliant, powerful sea creatures. We carry this amazing survival trait that has upheld our species through adversity.

Menopause is a superpower, and older women are evolved to lead.

This is where we can learn from orcas, and from the wisdom of the Coast Salish women seeking to reclaim their voices as fisherwomen, the haenyeo of Jeju continuing their centuries-old tradition of diving, and the single mothers of Zanzibar teaching their daughters and granddaughters to support themselves with seaweed and sponges.

Their passing along of knowledge is an act of hope as much as it is an act of survival.

Hope and the feminism of conservation

Yesterday took me from the seaside to the jungle of Zanzibar! I had a beautiful walking tour through the Jozani Forest, a conservation area that includes mangroves, monkeys, anteaters, and other amazing jungle wildlife. I got to see many Red Colobus and Blue monkeys run and jump around me in the trees, very curious and playful! More pictures and videos of them here.

It was also lovely to see the different species of mangroves on Zanzibar. I am very familiar with the 3 primary species of Florida mangroves, and it was great to see how they are related by genus to some of the 9 species of native Zanzibar mangroves. They are crucial to the local ecosystem as they hold the island sediment together with their roots and play a massive role in nutrient cycling, animal and other plant habitats, and wind resistance. They are threatened by deforestation.

Me on the mangrove walkways. Zanzibar is home to 9 native species of mangrove.

A Red Colobus Monkey in the Jozani Forest on Zanzibar.

Let me backtrack, though, to how my day started. The interview!

I met up with Okala at his restaurant about 30 minutes early, where he asked me if I had gone to any parties the night before and teased me when I responded that I’m too old for parties (truth is, I never went to any in my youth, either). He replied, “Age is nothing! You do what you want!” True thing, sir. I tend to want to go to bed by 9 pm.

On our walk to the home of the woman I would be interviewing, I asked Okala about how he knows the sponge farming women, about his life growing up on Zanzibar, and his connection to ocean conservation and eco-tourism. He told me he just wanted to protect what he knew was so important for his island and his people. This very much included women, especially single mothers, having a sustainable livelihood that gave them the independence of owning their own homes. It also meant eco-tourism. Okala brings in students and tourists from all over the world to exchange knowledge on sustainable aquaculture practices and to spread awareness of the importance of these practices; I believe this is why he is willing to work with me and my project.

We arrived at Nasir’s home, and she welcomed me with a hug. We sat on the floor of her living room, and Okala translated as I asked her a series of questions about her work. In caring for the sponges, she freedives (a Zanzibari haenyeo!) and spends about 3-4 hours a day in the water during low tide. Sponges are harvested from September through December, and the bulk of them are sold to tourist shops in the spring. She said that she feels a strong sense of camaraderie from the other sponge farming women in the community who form a co-op called Wakulima Wa Sponge Co-op. As a single mother of four children, Nasir is quite busy, as are her peers, and they depend on each other’s support. The biggest challenge in her work, she says, is climate change. She can tell that over the past 10 years alone, the sponges are suffering from bacterial infections that are only possible because of changing water temperatures. This has directly impacted how many sponges are harvested in a given season.

Me with Nasir, a freediving sponge farmer in Jambiani Beach, Zanzibar.

One of the last questions I asked Nasir: What is a source of hope for her when climate change is a threat to her livelihood?

Her answer: When there are good seasons, she feels hopeful. When there are not, she feels despair.

I had been thinking a lot about “hope” on this leg of the trip as I had been reading a book co-authored by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams called The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times. Much of the book takes a Socratic format as the co-authors muse on the definition of “hope” for what may feel like eternity to some readers. Is hope a feeling? A skill? An instinct? Jane calls it a “survival trait” and makes abundantly clear that hope is never a passive wish, but rather “requires active engagement.” For me, this rings true. I think hope is what brought me here.

But what about for Nasir? Is the farsightedness to hold onto hope beyond a single sponge season when the success of sponges equates to feeding your four children a privilege? Is hope also a privilege? Nasir perseveres, so perhaps whether she feels hope or not, her survival trait of tenacity is the kind of hope that Jane was getting at. Maybe that’s where I am chasing the meaning of “hope”, from a position of privilege to a position of necessity.

As I walked back with Okala, I asked him about how sponge farming compares to seaweed farming on Zanzibar in terms of success for the women. He said that even though seaweed farming produces greater GDP for Zanzibar, women make more in sponge farming. They can earn more per sponge by selling them at tourist stores than by creating and selling soap from seaweed. This didn’t make sense to me at first; seaweed is exported around the world, both unrefined and as soap. Sponges harvested on Zanzibar were not exported. The figures I had learned on my tour of the Mwani facility the day before suggested that seaweed would be more lucrative. Okala said that working for Mwani - a “large business” by relative standards - meant good benefits for the women, but less pay. There were other small co-ops of seaweed farming women in the area that fared better, but sponge farming was more lucrative still.

Some soaps I purchased from the Furahia Wanawake co-op of seaweed farming women in Paje, Zanzibar.

So here it is. The more corporate an operation becomes, the more wealth and power are driven away from women. I know this is a broad generalization, and yes, there are corporations run by women, and there are “good” corporations out there run by men, and so on. I know. But what I am pointing to is an overwhelming trend, especially in emerging economies, that corporations historically exclude economic opportunity for women and, by definition, exist for exploitative growth and dominance of their particular economic niche.

Am I just defining totalitarian capitalism? Yes. Am I judging the economic practices of a country on a side of the world I have nothing to do with? I might be, but that isn’t actually what I’m trying to do. In this and nearly every book she’s written, Jane Goodall lists the very first step towards change and hope in a world of destruction at the hands of humans as this: create sustainable livelihoods for people. Humans won’t stop cutting down trees, poaching endangered species, and relentlessly taking from nature if they have no other choice for survival.*

*I, for one, am not directing this toward industrial and corporate destruction caused by the United States. That’s not survival, that’s raw greed. We have many other choices for energy, for example, those that other countries have willingly taken up; we just apparently won’t do them.

What I am saying is that small-scale, community-focused work is what best supports both women and the local environment. They go hand-in-hand. Not the need for the fiction of endless growth. Not the need for dominance of an industry. In this way, conservation is a feminist movement. This is certainly not a novel concept, just one that I am cementing as verifiable from my first-hand observations. I worry that the larger a business becomes on Zanzibar, the less the women of the island benefit from it.

To be clear, it is dominance that I detest, not men. I may not have made this point lucid enough in my posts. I do not hate men. I am a mother of two wonderful sons. My sexual orientation favors men by about 70/30. There are wonderful men in my world who have helped me develop my sense of feminism throughout my adult life. What I hate is the definition of masculinity that necessitates dominance, which is necessarily violent. It gives me hope to encounter cultures that define masculinity differently (for the Maasai of East Africa, being a man means owning and herding a cow) and to see men define masculinity in their own ways; I don’t know how Okala defines masculinity personally, but I observed a man who is deeply committed to equality among those in his community and the sustainability of his natural environment.

Most of all, the women of this island give me tremendous hope. They are out in the low tide every morning gathering seaweed, both the Mwani Mamas and the co-op seaweed farmers. They smile, they go to work, and they support each other. They also put up with bright-eyed tourists like me asking them about “hope.”

One of the seaweed co-op farming women gathering seaweed in the early morning low tide.

This afternoon, I will do my final SCUBA dive on Zanzibar. Tomorrow, I fly away from the sea, concluding my research portion of the trip and my exploration of “the Sea and She”.

I have much to reflect on, and writing to begin, and will start doing so from the legendary beauty of Ngorogoro Crater on the mainland of Tanzania.

More to come from there.

No “pole pole”! I have to see a lady about a sponge farm.

The sun was out all day today! As was the wind. I was excited to start the day with a tour of the Mwani Zanzibar Mama’s facility here in Paje, and it did not disappoint. Well, almost.

The group of us tourists included me, a family from Belgium, and a woman from New Zealand with her partner, a local Maasai. Our guide was a friendly gentleman who first took us out into the tide to the seaweed farm itself, where three of the “mamas” were busy at work, mostly “weeding” away a parasitic green algae growth from the cultivated algae. The farm consists of wooden (or now, ideally, recycled plastic that can last much longer than the wood) stakes in the sand with spans of twine between them stretching several meters in length and forming long rows. The seaweed they grow and harvest is of four to five different varieties, all edible and mostly cultivated for pharmaceutical use, but also cosmetics and skincare products.

Some of the types of seaweed commonly grown on the Zanzibar seaweed farms, Cottonii and Spinosum.

He explained that farming seaweed had not been very lucrative for years, until it began to be used as an alternative to cloves in the 1970s and gained international demand for its many other uses in the 1980s. Prior to this, men weren’t interested or able to do such work for little pay, whereas women found it to be a good way to make their own money and gain some financial independence, and were able to have their children with them while doing the work. Today, it is a women-dominated industry, and the third highest generating industry in Zanzibar after tourism and spices. The biggest threats to the industry: climate change (of course), and storms. It takes about three months for a 1-inch “baby seaweed” to grow to a large bush full that he called “Bob Marley hair” (seaweed grows astonishingly fast that way), but a single large storm can obliterate entire farms like this, and the mamas simply set up a new one and start over each time. Brutal, resiliant.

One of the Mwani Mama’s, hard at work in the seaweed farm off of Paje Beach.

After our exploration of the farm, we got to see what next happens to harvested seaweed. It is first dried and then ground up before being used in making a variety of products on site, or shipped internationally (primarily to Japan and China, he said). We observed the tools used for grinding - simple, hand tools made of stone - and the factory room where soap is made. A couple more mamas were hard at work cutting large slabs of soap and shaping it into bars, and wrapping it in banana leaves.

Our guide told us that in the past, women were paid very little for their work and were unable to attain full-time employment status because of domestic and child care demands. Tanzanian religious and cultural gender roles are still very divided, but protections for women workers started going into place in the late 1990s and were further refined in the early 2000s. Now, women are guaranteed protection from gender-based discrimination in both part-time and full-time employment, have break rights for nursing mothers, and are entitled to three months of paid maternity leave.

(A little louder for the United States in the back.)

We sampled the soap, and it smells amazing. Different scents, of course - clove, ylang ylang, rose, lime, coffee, and lemongrass. Smooth on the skin and made from the sea. I am bringing many of these little bars back with me.

When our tour came to an end, I asked our guide if any of the Mamas spoke any English, or if he or anyone else at the facility would be willing to translate Swahili for a few minutes so that I could ask them a few questions. I explained the nature of my project and my intentions for it, and that I would be grateful for any time at all. He politely declined, saying that none of them speak any English and that he and the other staff are too busy with other tour groups or work.

Of course, I understood. They have a business to run; they don’t have time for some white lady who has all the markings of an “Eat Pray Love” excursion to pester them with what would probably sound to them like annoying lines of entirely irrelevant questions. A bummer, but c’est la vie. I was grateful to be able to see them do their work and to learn about the process.

Some of the soap making materials at the Mwani facility.

The Mwani facility store front. I ended up buying enough soap to possibly cost me a heavy checked baggage fee later. Worth it.

Back at my hotel, I sat by the beach and felt this nagging little thing in the back of my mind.

I am here to learn and write a story, I thought. I need to investigate harder, I thought. That’s what good journalists do, I thought.

I remembered another BBC article I had read months ago about women sponge farmers on Zanzibar and realized I hadn’t found a way to find them. The article gave names, but there was no real way to contact them that I could find. But now, I at least knew where these sponge farmers were relative to where I was. That’s something! Jambiani Beach, only 5 miles south of where I am staying.

I had no other information at all. But it was also only noon, and I had no other plans today. I could get a taxi down there, but I didn’t know how long I’d be gone, or really where, specifically, I was going. I just knew I was looking for a sponge farm, and a woman named Rajabu was involved. So best thing to do: I’d walk the beach. I put on a lot of sunscreen, packed my notebook, water, snacks, my GoPro, some village-appropriate clothing, should I need it (Islam is the dominant religion here and women are expected to wear clothes that cover the belly and shoulders, and down to the knee, when not on the beach), donned my signature “Sinatra hat” as my mom calls it, and off I went.

You should know that the beaches of Zanzibar are covered with tourists, and therefore covered with locals selling goods to tourists. This mostly includes watersport activities (on my long walk, I dodged a LOT of kite surfing lessons, some looked pretty dire), as well as Maasai looking to offer single women, in particular, security services or sell jewelry or other trinkets. They reach out for a fist bump and say, “Hey! Friend! Jambo! How are you doing?” I would nod, say “Jambo, all good, asante sana,” and keep going. I was walking quite fast, as I typically do, and they’d often yell out “pole pole lady!” for me to “slow down!”. But I was on a mission. I had a sponge farm to find.

“No, pole pole! Hakuna matata!”

Jambiani Beach.

This walk began to take a turn in my own mind.

What the hell was I doing? I had no idea where I was going. I don’t speak Swahili. I’m going on a 10-mile round-trip walk based on a 2-year-old article written by a real journalist, which I am not. What am I bringing to this? Even if I find these sponge-farming women, why would they talk to me? Because I’m also a mother? A divorced single mother, at that? Because I am a diver and marine biologist and love the ocean? Do any of these metrics mean we truly share anything meaningful in common? I live an entire world away, and am here funded by my school to uncover a throughline of aquatic feminism that may only exist in my overeducated little head, that privilege and luck have allowed the bandwidth to consider.

As I continued, I asked myself: What exactly is this voice? Was this my impostor syndrome rearing its ugly head as it periodically does? Was this the predictable discomfort of being in a radically new culture, traveling alone at that? A combination?

When I reached Jambiani Beach, I kept a lookout for what might be a sponge farm setup in the waters offshore. There were quite a few outrigger boats, but the tide was inbound and nearly high, which made finding any aquatic farm challenging. I continued walking, feeling like I might know something relevant when I see it. Buildings on the beach were resort after resort, restaurants intermixed, and I knew I should stop soon and ask someone at a hotel front desk or restaurant if they knew about any sponge-farming women nearby. But my legs were in such a rhythm, they kept going.

Eventually, I had to stop. I assumed it might take me a couple of tries before finding someone who knew what I was asking about; it was a long beach. I picked a restaurant and went in, and asked the host if he happened to knew about the sponge farming women. He nodded! He said I needed to go to Okala’s Restaurant...it was only 100m away, just off the beach.

I couldn’t believe the serendipity of my stopping point.

A small thatched hut, Okala himself was in the restaurant, and greeted me with a big high-five. I explained who I was, why I was there, and thanked him for the warm welcome despite my not being a restaurant patron. To my surprise, he quickly got out his phone and began to text some of the “sponge women”, who were apparently all out on the water. He explained that he is himself an ecotourism educator, currently hosting an intern from Turkey, and brings students from all over the world to learn new aquaculture methods, alongside the women who farm sponges and seaweed on Zanzibar (his exact relationship to them I have not yet determined).

Basically, he is the Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership of Zanzibar.

Turns out that the sponge women would not be back for a while, so he took my number and told me he would text me to set up a time in the next couple of days when they can meet. We chatted a little bit more about ocean sustainability, students, and my travels on this journey thus far. Okala gave me a flyer for his program and encouraged me to one day bring my students. Of course, I would love to. Now I would just return to my hotel and hope to hear back from him before I leave the island.

Okala’s ecotourism program on Zanzibar.

I walked back to the beach, took a big drink of water, and set out to trek back to “my” beach, Paje. My phone buzzed a few minutes later, Okala telling me that the sponge women are happy to meet with me tomorrow, I pick the time.

I drove my fist high into the air. I got myself an interview with the sponge women.

Is this how you do journalism? You go walking miles and miles with no idea what you’re doing, and you just ask questions until you find exactly what you need?

Is this the beginning of the road from vulnerable to venerable?

Or am I just a lucky idiot?

I met a new ocean, and she sang to me

Greetings from the Spice Island, Zanzibar!

Upon arrival yesterday, I sank my toes into the Indian Ocean for the first time. It feels different, smells different, and the colors exceed the vividness of pictures. I am staying in Paje, on the southeastern shore of the island, and there is a strong offshore wind that keeps kite surfers, parasailers, and outriggers constantly busy. There is a long reef breaker line offshore, and when the wind was calm early this morning, you could hear the singing roar of the waves breaking over it. This place is somehow both tranquil and yielding unrepressed energy.

My hotel, Paje Beach Apartments.

While my location is quite far from some of the primary tourist spots on Zanzibar - I am an hour’s drive from Stone Town, the spice farms, and Freddie Mercury’s birthplace - I unknowingly chose a hotel just a 5-minute beach walk from the primary reason I came to this island: to meet the women seaweed farmers, and their operation, the Mwani Zanzibar Mamas. Their seaweed farming is done just a few steps from my hotel’s beach, and it’s possible that I saw one of them farming this morning on my run. I have an appointment to meet with them on Wednesday morning for a tour of their facility and an interview. I cannot wait for this!

Early morning, possibly one of the Mwani Mama’s harvesting seaweed? Possibly not.

In my other time here, I plan to see how women are otherwise engaged with the sea, and do quite a bit of sea engagement myself. This morning I hit it off with a SCUBA dive right away. The PADI dive shop associated with this hotel is right next to my room, so another bit of logistical luck. I met both divemasters who would be going out on today’s dive, Ben and Arthur, as well as the other four divers: a young couple from the Netherlands, and a Norwegian father with his 11-year old son who was just learning to dive. Of course, I thought of my Jack, and how much I’d love to help him learn to SCUBA dive one day if he should want to.

Going into this, I knew the diving in Zanzibar would be beautiful. I had read about it and seen some pictures. But when you see pictures or watch documentaries, part of you expects there to be some slight exaggeration. Filters, enhancements, etc. Professional filmography makes a normal scene look its most extraordinary. Well, my friends, I am in no way/shape/form a professional anything with a camera. I have an excellent GoPro with a red filter, as advised for diving to temper the disappearance of red from the water column with depth. That is all.

And what I saw, through my own eyes before through the GoPro, was absolutely stunning.

I can’t believe I took this picture, either.

The water was a very comfortable 26 degrees C, clear up to about 20 meters, and the bottom was covered with some of the most stunning diversity of living things I have ever seen. Soft corals, hard corals, spherical Caulerpa green algae, dazzling fish that you’ve seen in Disney movies, nudibranchs, giant clams, and….my favorite part…a peacock mantis shrimp!! One of my favorite animals of all time. If you don’t know about the peacock mantis shrimp, then allow one of my favorite comic artists to introduce you; you’ll be glad you did. In all honesty, I kind of wanted the mantis shrimp to punch me and break my finger. It would be a tremendous honor. Alas, it chose peace, not violence.

Some of the incredible scenery from the dive. You can see the mantis shrimp in the center of the picture!

We drift dove for about 40 minutes before doing the same at a second dive site, and I was utterly mesmerized the entire time. I have been diving in the cold Pacific, the warm Pacific, the Caribbean, and yet this took my breath away (ok bad choice of words when talking SCUBA). I will be doing three more dive excursions during my time here and will most assuredly be posting more about those findings. If you want to see more pictures and videos from the dive (including my encounter with the mantis shrimp), check out my Instagram page.

The pace of my days is likely to be a little more relaxed here, which fits the Swahili mantra of “pole pole!”, meaning “slow slow!”. I shall endeavor to embrace this.

A jellyfish on the early morning beach.

The underwater giggles

It has been a very busy couple of days, but I promise this post will be worth it. I’ve been frequently (finally!) submerged, which doesn’t lend itself well to blogging.

As I had previously mentioned, I opted for an impromptu SCUBA excursion and am SO very glad that I did. I want to first note that going SCUBA diving when you and your dive buddy have a significant language barrier is not something I would recommend for an inexperienced diver. Yes, it is true that once submerged, SCUBA hand signals and communication is pretty universal. But getting on the same page at the surface is challenging when you are at the mercy of a translation app on your phone, which stays on the boat. In this case, as an experienced diver and PADI Divemaster, I felt confident in my own skills, and confident in my dive buddy’s skills and knowledge of the local area.

The SCUBA boat I went out on out of Seogwipo.

That said, communication with my dive buddy was rather funny at times. A welcoming man in his late 50s, my dive buddy is also an experienced divemaster, a fact he reassured me of via the translation app several times. On the way to the dive site, we mostly talked only in PADI lingo and just swapped certification words, while he took down several cigarettes (just a safe enough distance from the SCUBA tanks), and occasionally laughed at something that I couldn’t quite discern, maybe my feeble attempts at the few Korean words I kept practicing.

Once at the site, we saw a tourist submarine that I had seen docked previously near where I had watched the haenyeo work. Dive buddy got excited and pointed to it, saying “Submarine!”. It appeared that we would be diving close to the tourist sub, which gave me all kinds of ideas of nautical tomfoolery and fun that those of you who know me well can probably also envision. Maybe stage an underwater fistfight for them? Maybe just do the ‘going down an escalator’ or ‘running man’ in front of them? Pretend to guide the sub like a taxiing airplane? Good clean fun, from a safe yet visible distance, of course.

Anyways, we commenced our dive. He had warned me that the visibility was bad, but this wasn’t a deterrent for me. Having done much of my past diving in Monterey Bay, I know the trade-off that poor visibility can often provide: it usually means high water nutrients and so high density of living things. This was indeed the case in the waters of Jeju. We saw a spectacular array of different types of marine algae species, a huge diversity of soft corals, highly curious fish, and many of the invertebrates that I was more familiar with on the other side of the Pacific. The water was a bit chilly at our deepest point of 90 feet but mostly felt refreshing. My GoPro worked flawlessly (and the red filter helped, given the depth and visibility). I have many more photos and videos on my Instagram.

Some of the array of algae species seen in the waters of Jeju.

The diversity of soft corals was incredible!

At our deepest point, we heard some loud clanking. My buddy gestured “boat” to me, indicating the presence of the submarine. We then saw four bright lights flash at us (if you’re a Star Trek TNG fan…you know) through the murky water. Oh, the possibilities! Now this is where our communication truly came shining through. I timidly gestured that we swim toward the submarine, paired with a slight shoulder shrug. My buddy seemed to, for a fleeting moment, consider this. But then, much like a parent whose child has just spotted the candy aisle in a store, he shook his head and gently steered my elbow, pointing us in the opposite direction.

This made me giggle, almost to where I took water into my regulator.

All in all, a truly wonderful afternoon of SCUBA diving. I was grateful for this underwater experience, knowing that the next day I would learn to experience the sea in a very different way. Of course, I have experienced freediving and snorkeling countless times in the past. But this would be different. Learning from the haenyeo, I would be regarding the ocean in a highly specific way that was new to me. As a source of livelihood and nourishment, as a profession, perhaps in the way any fisherman/fisherwoman might, but with the added element of physical exertion and control of one’s body.

The morning before haenyeo camp, I enjoyed an iced coffee and yogurt at one of my favorite spots to sit and reflect. In the harbor behind me were several diving haenyeo. I continued reading a short book about them that I had bought some time ago (Sisters at Sea by Anne Hilty). In the book, Hilty emphasized how highly structured haenyeo society is with respect to rules about who dives when, where, and for how long. This has been the case for generations but is more so the case now since Jeju haenyeo attained their UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity designation. This is out of environmental sustainability first and foremost, but also to ensure that when the oldest, most experienced haenyeo retire, they will continue to be supported by the collective. I became intensely eager to know what some of those oldest haenyeo have seen, and what they think of the world now compared to when they first started diving.

My breakfast, a haenyeo statue, a haenyeo book, and haenyeo in the harbor (though you can’t spot them in this photo).

Haenyeo camp was an absolute dream. I met up with my group of other “campers”: 4 other women, all in their 20’s and 30’s, and just as eager to learn the ways of the haenyeo as I was. We gathered at a homestay run by a married haenyeo couple - a man and a woman. Yes, a haenyeo man! Something I thought was, by definition, impossible (haenyeo literally means “sea woman” in Korean). Turns out there are some (though very, very few) male haeneyo; of the 1500 active haenyeo, there are 11 male haenyeo, known as “haenan”, on Jeju. I suggested the nickname “haen-bro” for the male haenyeo, but alas my attempt at wit was very lost in translation, except to the English speakers in the group. Our haenan was a wonderful host, and couldn’t be more proud of his very experienced haenyeo wife (who sadly couldn’t join us due to an injury; she had to be in Seoul).

We had our first haenyeo dive with a young haenyeo who is also a SCUBA instructor. She, like most other haenyeo on Jeju, came to the island and trained at a haenyeo school; she was not born of a haenyeo mother. Nor would being a haenyeo be her primary job, as it is not lucrative enough. Most young haenyeo do so part-time, and do so for the passion of the work, the cultural significance, the female empowerment, and the sense of sisterhood, she and another young haenyeo woman explained. On our dive, we had some practice shells to retrieve from the bottom that were painted bright colors (there are rules about tourists taking living things from the sea). We had a lot of fun with this game!

We are haenyeo camp trainees! With our instructor, a real haenyeo (left). We are in a truck with our tewaks (the big orange floats with nets), on the way back from our dive.

The rest of the day consisted of shopping for and cooking an absolutely incredible fresh and traditional Jeju dinner. Our host took us through a market to pick up ingredients and taught us a cooking class, including how to prepare abalone. This process took a LONG time, not because it takes a long time to make delicious Jeju food, but because apparently we were very, very bad at chopping things (according to our host). It felt like we were on a cooking competition show at times, but we got through, teary-eyed from the onions, and it was entirely worth it in the end. In the dining space at the homestay, they also have a beautiful display of traditional haenyeo gear, attire, and artifacts. We learned of a rapid progression in haenyeo technology, for example, when neoprene and styrofoam were invented.

Traditional Jeju dinner. I actually made this! Abalone porridge, tofu and seaweed salad, and grilled abalone with vegetables.

Traditional haenyeo attire and equipment prior to the 1970’s.

The next day, we got to hone our skills somewhat with another dive. Everyone felt more comfortable in the water the second time around. It was wonderful to sometimes just hang on to my tewak and float for a bit, sometimes chatting with my “fellow haenyeo”, and wondering what generations of Jeju women would talk about when they floated together in the 3-4 hours each day spent at sea.

Our group of haenyeo trainees with our tewaks, ready to take on the sea.

What was especially profound followed our final dive: a lunch spent visiting with five haenyeo elders. These women were in their sixties to eighties in age and agreed to visit with us for about 40 minutes. I had many, many questions, but they speak zero English, and their Korean has a strong Jeju accent, so some of my Korean-speaking classmates even struggled to understand them. With the help of our intrepid coordinator Soyoung, some translation was possible. They told us how they became haenyeo when they were 9, 15, or 20 years old. One woman travelled to Japan for a period of time to be a haenyeo there. They all said that the environment is the single biggest thing that has changed: less catch, less wildlife, warmer waters. This is, of course, unsurprising. They had a kind of unique beauty about them, weathered by the sea and entirely part of it. I asked them if they could do diving in any other waters in the world, where would they go? They all replied: nope.

Our haenyeo group (standing) with our haenan host (right) and the five elder haenyeos (seated).

As I leave Jeju, I am immensely grateful for every second of my time on this island. I will absolutely return one day, hopefully with Jack, as I think he would have so much to learn and gain from it. The island charmed me in so many ways, and I learned more than I have yet fully processed. I came across a poem by a young Korean poet named Park Joon (this was in the Korean Air inflight magazine I was browsing through on my flight from Jeju to Seoul), and it just felt apropos:

By Park Joon

And now, I’m off to Zanzibar.

Yes, go chasing waterfalls

My Jeju life is shaping into a fascinating routine (I know, how can there be a “routine” with 3 out of 6 days spent in a place?). Perception of time is such a funny thing. Seogwipo is starting to feel like my “hometown”; I know my way around my neighborhood, I have my favorite coffee spot, and my favorite running route. It feels as if I have been here for weeks. Unfamiliarity has a perplexing way of slowing time down in the same way that the familiar speeds it up. My time on Whidbey Island absolutely flew by; while I was learning new things and getting to know a new town and island, it was my home region, and what can be more familiar than being with one’s parents and child? Compare that to being on a new continent, across the world, immersed in a new language and culture, with almost no familiarity. It is so damn awesome. My only point of familiarity: the sea. She remains my constant.

Side note: Much to my delight and chagrin, I made the World Marathon Majors lottery for the NYC Marathon this fall. This is excellent; New York is one of the very hardest marathons to get into by lottery, and I am not the spring chicken, speedy runner that I used to be, who can get fast time bonuses or whatever anymore. But also, it means I have to do SOME degree of training while on this trip. Which is not ideal, especially given the combination of schedule, jetlag, heat, humidity, and my desire to focus my attention elsewhere. At the same time, I have also always enjoyed experiencing a new place from a runner’s perspective. So this morning, I decided to run speed repeats on the Saeyeongyo Bridge so that I could also watch the haenyeo working in the water. There were two haenyeo working in the water at the time, and I thought it fun to gamify my run a little: whenever I heard one of them whistle, I accelerated. Suffice to say, they whistled enough that I was thoroughly exhausted after 1 mile of repeats (to be fair, anaerobic work is my weak spot). They unknowingly helped coach me and played a role in my preparation for the NYC Marathon.

Onward: I ventured out of my “hometown” later in the day. Found some more waterfalls, a botanical garden, and a beach, 30 minutes to the west. The Cheonjeyeon Waterfalls were a set of 3 spectacular falls amidst a walkway of bridges, all with paintings and carvings depicting the search for waters of “eternal life”.

One of the stunning falls at Cheonjeyeon. There are rock formations like these in various parts of the island.

The beach was pristine and provided a nice reprieve from a very active morning. There were families, a nice father and daughter from Turkey who were visiting for a dentist conference, and a pack of Korean teenage boys who delighted in knocking each other off of flotation structures in the water. The sand is a unique blend of fine white grains and the coarse black basalt from which the island was made. The water felt exquisitely refreshing.

Jungmun Saekdal Beach

From there, I found my way to the Jeju Botanical Gardens, a diverse curation of flora both inside a uniquely designed greenhouse and in a series of outdoor walkways, each with a different regional or ecological theme. It was peaceful to explore and the sections on native plant life, in particular, deepened my appreciation for the natural uniqueness of Jeju.

Inside the main greenhouse at the Jeju Botanical Gardens

My evening activities included finding a haenyeo-owned restaurant and enjoying a seafood meal. The hostess (who may or may not have been a haenyeo, that wasn’t entirely clear) did not speak English (most here do not), and my capabilities in Korean essentially just allow me to say ‘please’, and ‘thank you’ in situations of ordering food, and so I just ordered what she told me to. This ended up being a large plate of sliced lobster tails and abalone, garnished with vegetables and various sauces. It was indeed very fresh and delicious. At the Camp on Friday, I look forward to learning about food preparation and how certain types of foods are selected and paired.

Haenyeo art in the restaurant

Next up: SCUBA diving on Thursday!

I hadn’t planned on doing any SCUBA diving on Jeju, but upon arriving, it made no sense not to. There are dive shops on practically every block, and I found a PADI-specific shop very close to my hotel. I went in yesterday and spoke through a translation app with the young woman in the office to schedule the dive. She was very nice and the translation app mostly worked very well. Before leaving, I said into the app that I was on Jeju to go diving with the haenyeo and hadn’t planned on doing any SCUBA, but am excited to do so. I think the app didn’t properly translate “haenyeo” specifically, and maybe instead said “women divers”, and I think the she thought I meant that I only wanted to go diving with other women. She then spoke back into the app to reassure me that, despite the shortcoming of being a man, the diver leading my trip is very experienced and has many certifications. I gave a mildly-approving nod.

A truly Jeju conversation.

Jeju 4.3 & Protest

Warning: this post contains mentions and references to intense violence, including sexual violence.

I am dedicating a specific post to the Jeju uprising and massacre on April 3rd 1948 (known commonly here as “Jeju 4.3”), as I have seen frequent memorials to this historical horror around the island and, like most if not all of you reading this, had no idea what it was prior. But the more I read about it, the more it settles within me, the more it coalesces with my befuddled fury over what is developing in my own country. Nearly all of the information I’ve found on this event has been on Korean-based websites, very few US sites, but good thing I’m currently in South Korea.

One of the approximately 90 memorial sites on Jeju Island dedicated to Jeju 4.3, Seogwipo.

In a nutshell, following decades of Japanese occupation of Korea and the end of World War II, the US Army established a military presence and control of Jeju Island. Many left-leaning Koreans on Jeju were vehemently opposed to the formation of separate Korean governments as would follow in the upcoming election, but the United States’s sole focus was snuffing out any and all communist leanings or sympathies, as it was everywhere in those years. The US Army bolstered the police presence on Jeju to try to manage this concern, and also imposed a punitive restriction on barley imports following a poor harvest season. Tensions escalated, and protests and mass arrests ensued.

In March of 1947, police fired gunshots into a crowd of protesters, killing six civilians. The US Army did nothing about this; no repercussions for the police officers who fired the shots. This enraged the citizens, and violence erupted around Jeju. The US Army armed and backed right-wing groups to counter what they perceived to be a rising “Red Island”. This was the tinder to ignite a massacre that would cost Jeju Island 10% of its population.

On April 3rd, 1948, armed rebels attacked police stations and the powder keg of both right-wing and left-wing forces on Jeju exploded into a bloodbath of murder, rape, the burning of farms and villages, torture, and destruction with a death toll of around 30,000. During this time, the US Army was the governing authority of Jeju, and did nothing to prevent the violence. According to the foreign policy journalist organization Inkstick - one of the only US sources on Jeju 4.3 that I could find, with many citations from the 2000 Jeju 4.3 Committee for Investigation - the US Army wasn’t apathetic, it was strategic: “One US official saw the 4.3 uprising as an opportunity for South Korean military forces to gain combat experience.”

The United States was ultimately successful in the containment of communism to the north. The election in May of 1948 secured South Korea as a separate entity from North Korea. To once again quote Inkstick, “Jeju had the lowest voter turnout in the country, the highest election-related injury and death rate, and the election results were deemed invalid.”

To be clear, I am not suggesting that the division of Korea was good or bad, or making any statement about communism. That isn’t the point. A foreign occupying entity - the United States - not only oppressed the voices of Korean citizens on the fate of their country, but it also actively participated in their mass execution as a way of controlling the outcome of their election.

Furthermore, it weaponized their protests and incited their civil dissidents as a means to an end that had nothing to do with the well-being or future of the people of Jeju Island.

Prison camps were all the rage under the police state and US Army-controlled Jeju in 1947-1948.

Now you know why you haven’t heard about it.

The horror is indisputable. The scene and the players are predictable. The inhumanity is familiar.

In my 20+ years of teaching science, there are often these lunch table conversations where my teaching colleagues and I jest about which subject is the most important one. As the scientist at the table, my argument is always easy: you can’t write plays or learn history or make art without clean water or air, can you? Isn’t climate change our worst problem? Etc etc. These kinds of silly debates are always a false dilemma anyway. We all need each other. Without writing skills, science doesn’t get communicated, and without understanding history, people vote for administrations who defund all the science, and without art, none of this insanity is remotely bearable.

But I have to give this one to the history teachers. They are the ones who say, “Hey, here is this thing that has happened many times and here is what it looks like.” And whether on every bookshelf in the West depicting 20th Century Germany, or on scattered memorials across an island remembering 20th Century South Korea, or on countless other means of communicating the truth of our past, history always says “yep, yep, here is what the thing looks like.” And even when Hollywood says, “Look! Here’s what the thing looks like. We can even dress it up as Star Wars and make it go pew-pew with lasers so you’ll watch it.”

We watch it, we cheer for the “good guys”, and then, we (Americans) either vote for the fascists or for the team that appears to do not a single goddamn thing about the fascists. A concentration camp is opening in Florida this month. Our Secretary of Homeland Security believes Habeas Corpus to be precisely the opposite of what it means. There are too many examples of madness to name, and yet right this second, I can’t even conjure a nice round third to bring balance to this paragraph because of the daily onslaught of fresh “Breaking News” horrors in my email inbox from the NY Times has me overwhelmed with options. Someone go spin a roulette wheel, it could seriously be anything.

Yes, I am well aware of the fact that these little slivers of what are mind-numbingly stupid at best and outright inhumane at worst are a far cry from a 30,000 dead bloodbath. How quickly did Jeju 4.3 escalate, by the way? And my dear frogs, how does the water in the pot feel right now?

We turn on the news, and it says, “Protestors are a problem.” That tells you where we are in this story. In the German resistance story, in the Jeju story, in the Andor story, history or fiction, the mile markers are all the same.

Another Jeju 4.3 memorial at Cheonjeyeon Falls.

So far on my trip, I have not encountered any other Americans (there must be some here somewhere, but we certainly aren’t the primary tourist clientele for Jeju). This is simultaneously isolating and liberating most of the time, but today, it felt heavy. I felt a deep shame for my country and the only notable role it has played in Jeju’s history. The people of Jeju deserve a formal apology from the US government, and I so wish it had happened during the Obama or Biden administrations; it will certainly not happen now, and sadly, survivors or anyone who would remember Jeju 4.3 are not likely to be around too much longer to witness such a thing in the future (except some of the haenyeo, maybe. They seem to be quite badass at longevity, too).

Do we ever get this right?

Another Jeju 4.3 memorial at Cheonjeyeon Falls.

The haenyeo! They’re everywhere!

I am finally writing from Jeju Island, South Korea! After a lot of flying and a layover in Beijing (why not Seoul, you ask? Airlines are weird and it was somehow faster and less complicated this way), I arrived on June 30th in the afternoon. I am staying in the city of Seogwipo, on the southern and opposite side of the island from the airport. It is the second largest city on Jeju, and much larger in population than I had imaged from my research. This is definitely the busy tourist season for Jeju; it is considered “the Hawaii of Asia”, at least to the Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese, as a vacation spot. I can certainly see why: palm trees, beaches, unique rock formations, unique museums (like Hello Kitty and Action Figures and Seashells), and lots of resorts. My room with a view certainly can’t be beat.

My hotel room view in Seogwipo, Jeju. The next morning I could see haenyeo in the harbor.

But you all know why I’m here. I’m here for the women. And their spleens. Yes, those freaking amazing spleens that let them be functionally more seal than human for the purposes of freediving. I was hoping to come across a haenyeo workshop/base camp/whatever they call it (I don’t yet know the terminology) before I meet up with the group I’ll be learning from, the Nomad Her Haenyeo Camp on Friday July 4th. But I didn’t expect to find them as easily and ubiquitously as I did. I set out in the morning to find the Saeyeongyo Bridge connecting the mainland to Saeseom Island for a nature walk and came across a building that had all the markings of haenyeo activity: collecting nets, round orange buoys used as floats for their collecting nets, running water tanks for fresh catch, and a giant mural with haenyeo on it was a slight giveaway.

The Saeyeongeyo Bridge, with haenyeo diving in the water to the left!